How to measure the impact of zoning on housing in your city

and why "zoned capacity" is a bad way to do it

Planners do important work moulding how our cities grow. They use zoning and master plans to balance the need for housing where people want to live with the need for efficient transport and other civic infrastructure.

But how do you balance those trade-offs? It’s common for cities to quantify when a freeway might hit the point of congestion, or when a sewerage system might overflow, but it’s much less common to measure how much damage is done by not allowing people to live where they want to live.

This post outlines a novel methodology I constructed with the help of the team at YIMBY Melbourne (including superstars Paul Spasojevic and Jonathan O’Brien) to measure the barriers created by different levels of restrictive zoning in cities.

While there’s strong evidence that zoning limits the overall supply of housing, you don’t need to believe this fact for our methodology to be useful. Even supply sceptics agree that planning changes where housing is built in a city – often away from where people most prefer and towards where planners think is better in the long run.

The distortions created by zoning may well be justified, but to know for sure, planners should be required to measure these distortions as part of any zoning or strategic plan. Where the distortions are greatest, more care should be taken to ensure the costs of restrictive zoning are worth the benefits.

The downside of zoning

Most westerners live in detached homes. In the absence of restrictive zoning, every home sale would be a bidding war between a potential single homeowner and people who each want to pay less to share the land by building apartments or townhouses.

Where land prices are low, the single homeowner will likely win out. Constructing new apartments is expensive, and if the price people are willing to pay to live in apartments in the area is low then the homeowner is likely to win at auction.

But as a city becomes more popular, the number of people and the price they’ll pay to live in apartments increases and so those apartment buyers bid up the price of the land until they can outbid prospective homebuyers and start building.

In areas with restrictive zoning, the price of land doesn’t respond to demand from apartment dwellers. Apartment prices in an amenity-rich area might be so high that you could justify a 100-storey building, but if it is illegal to build then the price of land will only reflect what somebody is willing to spend to use that land as a single-family home.

The gap between what people would be willing to pay to put apartments on a block of land and the current price of that land is an effective measure of how much zoning is restricting housing on a given lot.

Planners should measure the distortions created by zoning in their city

With the right data, measuring the costs of restrictive zoning in cities is relatively easy. For a given plot of land, all you need to do is estimate what the land is currently worth, what an apartment on that land would sell for, and the cost of building apartments at various building heights. If enough density is permitted, the price of land should reflect these calculations. Where there are super-profits to be had by building on a block of land and yet those profits haven’t either jacked up land prices or lowered apartment prices, then zoning is restricting supply on that lot.

Unlike other measures of distortion created by zoning, this method allows us to go beyond comparing the costs of current zoning to a fictional world without any zoning at all. Planners can also compare how current zoning compares to other politically achievable zoning outcomes.

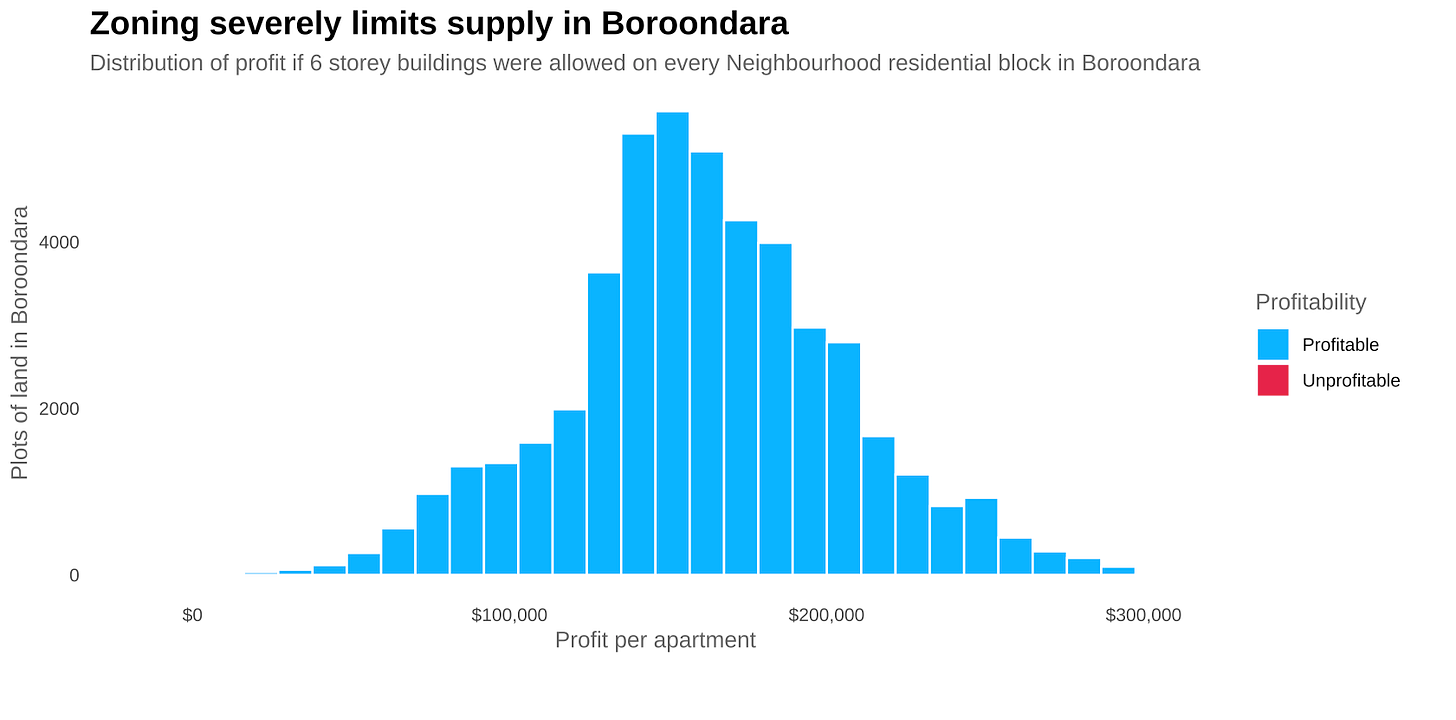

YIMBY Melbourne wanted to see how much Melbourne’s current zoning restricts supply compared to 6-storey height limits being rolled out in Sydney. When we did that in one of Melbourne’s richest areas (Boroondara) the results were stark. If a developer could build 6 storeys in this area they could make on average $160,000 per apartment built, even after their usual profit goal of 20%. This kind of extreme profitability should either make apartments cheaper or be priced into the land. The fact that neither has happened shows that zoning is restricting supply.

The super-profits available suggest that zoning in Boroondara is incredibly restrictive. But the same zoning might not be restrictive where demand is lower. In Brimbank for instance, where there is much less demand to live in apartments, zoning to 6 storeys would not change development much. People who want to live in a house in Brimbank would out-bid apartment dwellers, even if we allow 6-storey tall buildings. As a result, we can say that the existing zoning does not significantly reduce the supply of new housing on existing lots in this area.

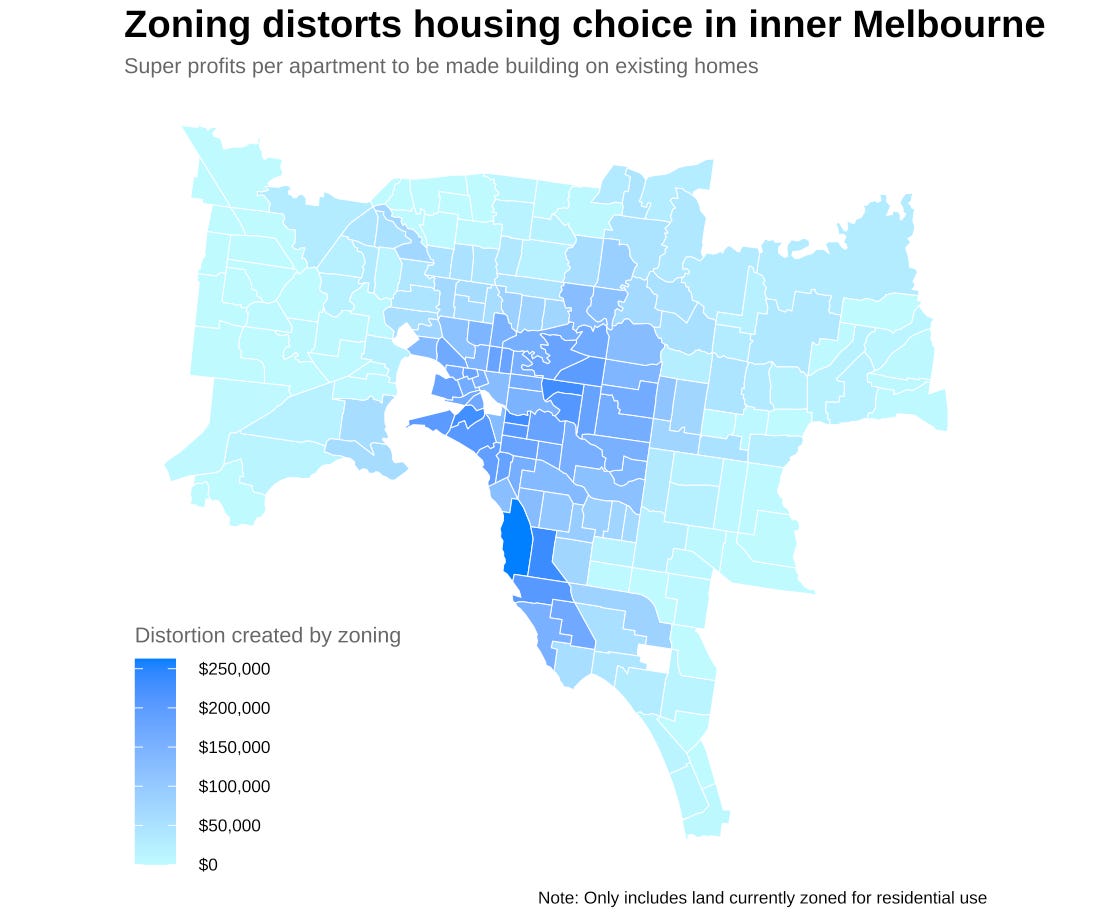

We’ve calculated the distortions created by zoning for inner and middle Melbourne and the situation is dire. Zoning in areas like Boroondara is distorting the value of land, to the detriment of people who want to live in apartments.

Planners should quantify the costs of restrictive zoning regularly and publish their findings. Measures of distortion created by zoning in each local area should be a metric that keeps planners up at night. This figure should be calculated for each neighbourhood every quarter, and when the number grows and yet planning applications do not then the warning lights should flash red.

The costs of zoning should drive housing targets

When setting housing targets for a city, the distortions created by zoning should be the most important variable in deciding where homes should go. In Melbourne, we allocated the city-wide housing target to Local Government Areas based on the total number of super-profitable apartments that would be possible in each area if 6 storeys were allowed near train stations and tram stops.

The targets ensure that when the state upzones an area, local governments are prevented from using other planning measures to slow construction. The targets are higher in areas like Boroondara where there is ample public transport, lot sizes are large and demand for apartments is high.

In expensive areas, we opted to recommend less up-zoning in lots that were far away from public transport, because the cost of building more extensive transport infrastructure in those areas risks being greater than the harm created by restrictive zoning. But this tradeoff was merely a ‘rule of thumb’ for YIMBY Melbourne. In Victoria, the state government recently merged the Department of Planning with the Department of Transport so that these kinds of trade-offs could be better measured.

“Zoned capacity” is a terrible way to measure the effects of zoning on a city

There's another method that is popular amongst planners to decide whether zoning is affecting supply. Planners will count up the theoretical maximum number of homes that can be built using existing zoning (zoned capacity), and if that figure is greater than an arbitrary housing target for the next few decades, they will declare that zoning is not restrictive.

This method was popularised in Melbourne by Michael Buxton, Joe Hurley, and Kath Phelan. We can see this idea used in Boroondara’s housing strategy:

However a zoned capacity greater than the need for housing does not prove that current zoning is appropriate. Even if zoned capacity exceeds predicted demand for housing it can be restrictive for several reasons:

1. Some land will never be developed and so the ‘zoned capacity’ provided by it is not real

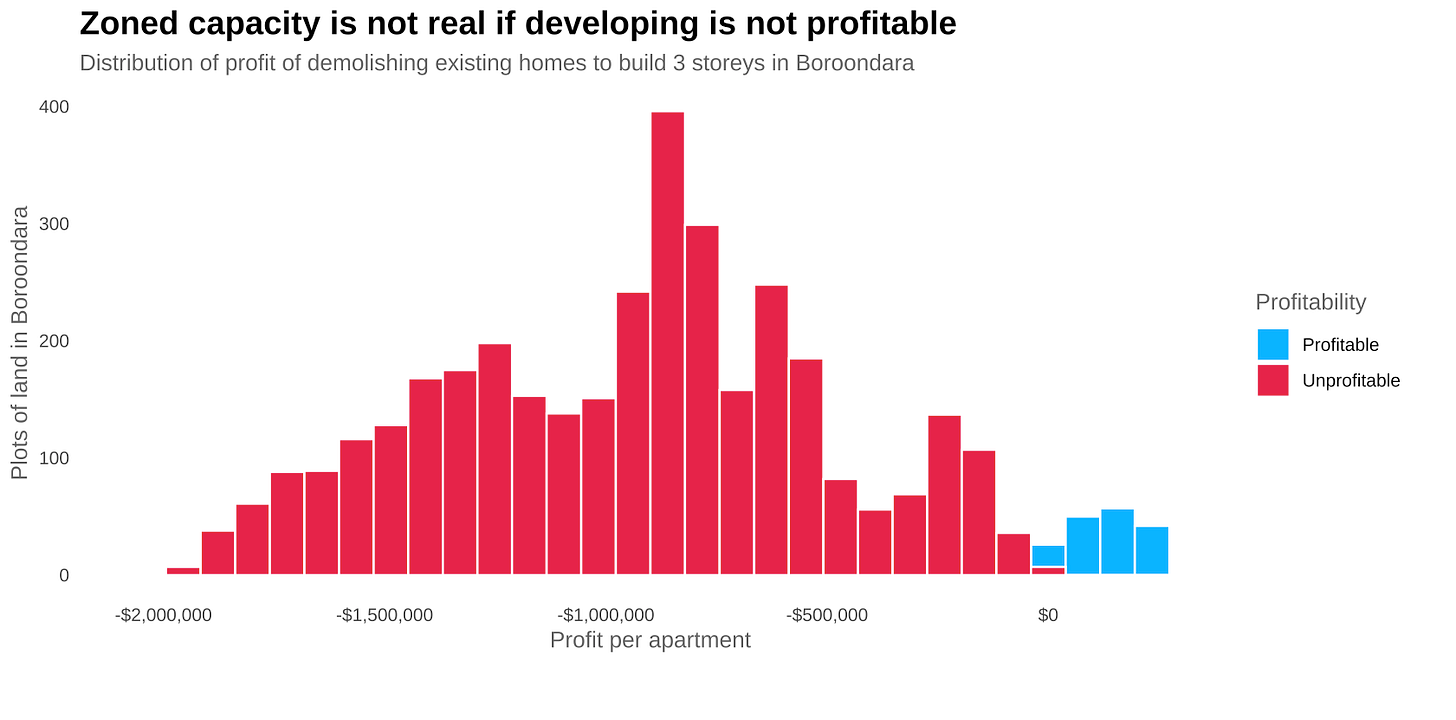

The existing homes on a block of land have value. There are some homes in Boroondara where 3-storey apartment blocks are permitted, but our analysis suggests that once you pay for the land, demolish the house, and build something new there isn’t enough profit to make it worthwhile.

The homes in the graph above are from just a single zone in Boroondara but represent 12,000 homes of Boroondara’s zoned capacity. Almost all of it is unbuildable. The only way to make 3-storey buildings on this land profitable would be to make housing so unaffordable that the price of apartments increases significantly, harming renters who rely on apartments to stay housed.

Even if there are technically just enough “profitable” apartments to meet demand, zoning still restricts supply. That’s because not every block of land is suitable for new housing. Some people love their homes and will refuse to sell. Some existing non-residential uses for land might be very profitable or beloved by the community, making development unlikely. Additionally, council heritage and neighbourhood character guidelines may also act to limit what can be built on a given block of land.

Each of these factors chips away at the real zoned capacity of a given area. For zoned capacity to actually enable enough housing to be built, the number of potentially profitable apartments in an area must be many times the number of homes a community needs.

2. Housing ‘need’ numbers are often made up.

Boroondara estimates that 9,400 more homes will be needed in their local government area over the next 15 years, but these housing needs figures are often made up. In Victoria’s case, the population estimates for each area usually come from the state government's Victoria in the Future projections, which are designed to predict how many people will move into an area.

But these projections are based on each given area's “capacity to absorb extra population” – meaning that zoned capacity has dictated future population projections, which are now being used to justify existing zoned capacity.

The real number of apartments that Boroondara needs is however many will make rents cheap. But zoned capacity does not provide any insight into what that number might be.

3. Rationing zoned capacity gives a monopoly to developers and encourages land banking.

Despite the limitations outlined above, the current zoned capacity of 65,000 in Boroondara means there will be some suitable lots to build on. But because the need for housing and the zoned capacity are so close to each other, the people who own the best lots for development are able to maintain a near-monopoly on new housing in the local area.

If you hold one of the only possible lots that apartments can be built on in a local area, it is much more tempting to hold off on building in the hope that prices will be higher in the future and your profits will be greater.

Where upzoning is broad, land speculators have to look over their shoulders and consider the many more nearby land-owners who might beat them to the punch, discouraging speculation and lowering the cost of new apartments.

In the example of Boroondara above, land prices have been suppressed by $160,000 per potential apartment because of highly restrictive zoning. Narrow upzoning would cause property prices to rise by around this much, as land speculators know that there are future residents in the area who will have no choice but to buy an apartment on their land. If there is broad upzoning then apartment buyers will be able to play landowners off against each other, and as a result they will get much more of that $160,000 in the form of cheaper house prices and lower rents.

4. Only allowing a small amount of “zoned capacity” denies people choice

When planners limit zoned capacity to a number that’s only slightly higher than what needs to be built, it denies people choice. Some people might prefer to live on a side street, or they might prefer to live in a particular part of a local area. Limiting zoned capacity means they are denied that choice and will end up with housing locations that don’t suit their needs as well.

Planners attempt to account for this by recommending a diversity of housing options in their strategic plans – but it’s impossible for them to perfectly predict what kind of housing people will want and where. Increasing zoned capacity to many times future demand will maximise choice, and reduce the number of tradeoffs people have to make when choosing where to live and work.

For all of these reasons, big changes in zoned capacity are needed to shift the needle on housing supply. The exact amount of capacity needed is unknown and will depend on what type of zoning capacity is provided, building costs, land values, and demand for apartments in a given city.

But Auckland does provide us with some clues on how changes to zoned capacity affect prices. In 2015 Auckland tripled its zoned capacity, and over the next 6 years the number of homes in Auckland increased by 4.11% more than would have otherwise, lowering rents by 14-35%.

YIMBY Melbourne is proposing that the inner and middle suburbs of Melbourne be upzoned such that their zoned capacity is increased 7-fold. Many of our upzoned areas include the most desirable land in Melbourne, increasing the chance that the zoned capacity will be used to build new homes.

Giving up control

One of the hardest things about broad upzoning is that it requires planners to give up control.

Some of the most beautiful cities in the world have streets with rows of buildings all of a similar height. These symmetrical streetscapes are largely the result of technological limitations that made tall buildings difficult. For instance in Brooklyn, brownstones are usually a similar height because pumping water to higher levels was expensive. In Europe, fire regulations and a lack of elevators drove many old cities’ building heights.

Planners often dictate the maximum heights of buildings to achieve similar aesthetic outcomes, even when they do allow tall buildings to be built. For instance, the new Melbourne Suburban Rail Loop master plans have a complex set of zones designed to achieve aesthetic outcomes unrelated to the area’s overall density:

Planners no doubt hope that demand for housing is so strong and zoned capacity so limited that apartment buildings will be built up to somewhere approaching the maximum zoned capacity of each zone. As a result, their preferred streetscape aesthetic will be achieved.

But broad-based upzoning means giving up control. If instead of allowing one street near Box Hill Station to have 20 storeys we decide to allow 6 storeys along the whole train line, planners will not be able to decide where new apartments go. No doubt we will end up with streets where half the homes are detached and the other half have apartment buildings of various heights. The process will not be ordered, but it will mean that there are many more potential sites available for people who want to build apartment buildings, so the cost of upzoned land will be less.

Giving up some aesthetic control means creating a city much more like Tokyo where building heights differ markedly even on lots next door to each other. In these cities, planners need to constantly measure demand and supply changes, and design the delivery of infrastructure in response to these measurements—rather than trying to control demand and supply itself.

While there are real costs to more permissive zoning (e.g. local traffic congestion), these costs should be measured and balanced against the distortion created in housing markets by the zoning status quo. This is a marked improvement on current planning regimes, which mostly neglect to measure the costs of decisions at all.

By broadly upzoning and enabling more choice, cities everywhere will empower more people to live where they want to live.

This post refers to 'zoning' to maintain international relevancy, but for the purposes of Victoria's planning system it includes zoning and overlays (including heritage overlays!)

Great discussion Jonathan, thank you. I particularly appreciate your point about how limited upzoning allows developers to hold a monopoly on future development, whereas broad upzoning creates competition that makes it less practical to landbank.