Tackling homelessness in Australia

Homelessness is getting worse in Australia. About 50 in every 10,000 Australians were homeless on Census night in 2016. Rough sleepers are the most visible homeless, but they account for only 4 per cent of Australia’s homeless. More often, homeless people are living in homeless shelters or staying temporarily with friends or family. Almost 38 per cent of all Australians classified as homeless by the Australian Bureau of Statistics are living in ‘severely crowded’ dwellings (places that would need to have four or more extra bedrooms to properly accommodate the people who usually live there).

Homelessness is highest in Northern Territory, more than 10 times worse than any other state and territory. The rate of homelessness has risen across most states, and is up 10 per cent nationwide between 2006 and 2016. The largest increase came from a larger number of people living in severely crowded dwellings.

There has been much attention on the emerging homelessness crisis among the elderly. But most homeless Australians are young: about 58 per cent are younger than 35 (Figure 2.2). About 81 in every 10,000 Australians aged 15-24 are homeless, falling to 39 in every 10,000 among those aged 55-64. In fact people aged 19-34 account for 65 per cent of the increase in homelessness in Australia over the five years to 2016, and men account for 69 per cent of the increase.

In contrast, relatively few older women are homeless. But the risk is rising: nationally, rates of homelessness increased fastest over the five years to 2016 among single women entering retirement age. Declining rates of home ownership among younger poorer Australians, together with the lower retirement savings of many women, increase the risks that more older women will suffer poverty and homelessness as they approach retirement.

How do people become homeless?

Homelessness is not an individual problem. A person who becomes homeless is likely to have faced a difficult combination of economic and social circumstances, but a key ingredient is almost always expensive rent. Australian evidence shows that the risk of a disadvantaged person becoming homeless increases from 2 per cent in areas with plentiful cheap housing, to 17 per cent in areas with high rents.

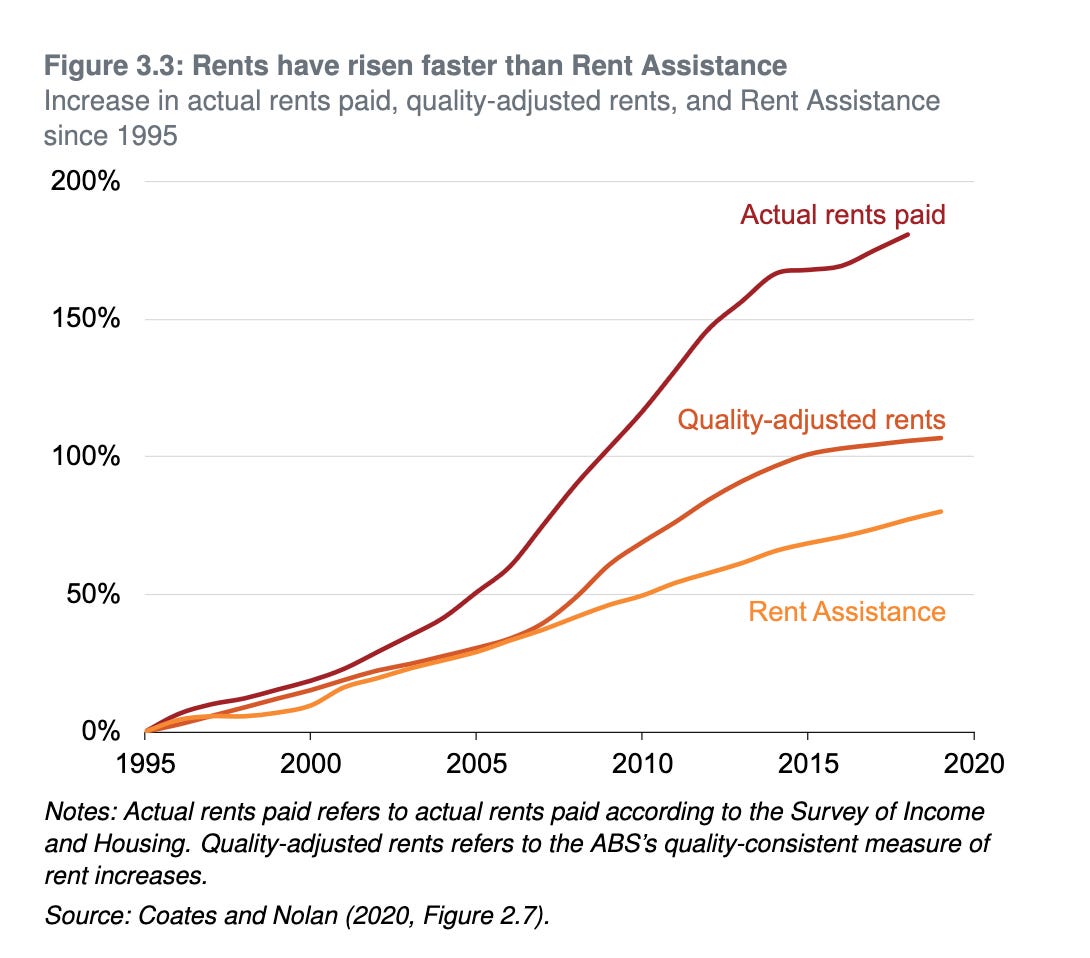

And rents are getting more expensive. While private renters in Australia are spending a similar share of their income on rent, the disappearance of social housing means that overall, the bottom are spending more.

The social security safety net has fallen out from under us

Income support system plays an important role in alleviating financial stress and poverty for low-income Australians. Yet while the Age Pension, Parenting Payment, Carer Payment, and Disability Support Pension are indexed to wages, JobSeeker, Youth Allowance, and rent assistance only increase with inflation. These payments have therefore become woefully inadequate as a safety net for unemployed Australians. Unlike wages or pensions, JobSeeker has not increased in real terms in more than 20 years.

This has ‘squeezed’ the living standards of people living on JobSeeker relative to the rest of the population. Households of working age receiving JobSeeker are under much more financial stress than households receiving other welfare payments.

At the same, more people are having to rely on JobSeeker who would have been better supported by the social welfare system in the past. Eligibility for the Parenting Payment and the Disability Support Pension has been tightened in recent years. Changes in assessment rules for the Disability Support Pension in 2012 have especially hit Australians approaching retirement age who have musculoskeletal health problems. The changes coincide with an increase in the number of older people on JobSeeker.

Social housing can also help

The public health crisis caused by COVID-19 has resulted in an unplanned trial of a ‘housing first’ approach. Many people sleeping rough who would have previously been denied access to safe housing were given hotel vouchers, to help them socially isolate through the crisis. By one estimate rough sleeping was reduced by 60 per cent almost overnight.

But people rough sleeping cannot stay in hotels forever. Despite its importance to vulnerable Australians, Australian governments have invested little in social housing over the past two decades. The number of social housing dwellings has barely grown over that period, while Australia’s population has increased by 33 per cent.

Tenants generally take a long time to leave social housing: most have stayed for more than five years. And when people do leave public housing, it is rarely by their own choice. In 2012, only 18 per cent of people leaving social housing voluntarily entered the private rental market or bought their own home. As a consequence, there is little ‘flow’ of social housing available for people whose lives take a big turn for the worse, and many people who are in greatest need are not assisted. The result is that fewer Australians are living in social housing than in the past, and every year proportionally fewer social housing units become available for new tenants.

How to tackle Homelessness in Australia

There is a powerful case for more Commonwealth Government support to reduce homelessness and help house vulnerable Australians. But housing subsidies are expensive and not all policies are equally effective. The Government should prioritise reforms that target those most in need, and deliver the biggest bang for taxpayers’ buck.

The Government should give priority to constructing new social housing for people at serious risk of homelessness, replicating the success of ‘housing first’ programs abroad. Social housing is particularly effective stimulus, but does come at a cost. Once more units are constructed, they should be reserved for those most in need, and at significant risk of becoming homeless for the long term.

Boosting Commonwealth Rent Assistance by 40 per cent is a cost-effective way to help the much larger number of lower-income earners struggling with housing costs.

Housing will become substantially more affordable for most low-income Australians only if we build more of it. The Commonwealth Government should provide incentives to the stats to fix planning rules that prevent more homes being built in inner and middle-ring suburbs of the capital cities. More private housing can and does help those on low incomes by lowering the rents they pay. And lower rents reduce the risk of homelessness for those already vulnerable.

Housing vulnerable Australians poses substantial policy challenges. Past governments have refused to face up to the size of the problem because they feared doing so would fuel demands for massive new expenditures on housing. But the challenge is not insurmountable. Policy can make a difference, but only if we make the right choices.